This year, the Mississippi River flooded for more than 6 months, unprecedented in both length of time and volume of water. Researchers recently announced that this year the excess fertilizer from farm fields carried to the Gulf of Mexico helped in the development of a low-oxygen, “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico that covered an area of 6,952 square miles – the 8th largest ever measured!

Slow moving species that live on the ocean floor cannot escape a dead zone and often die. In areas that are repeatedly in the dead zone footprint, the diversity and number of species found on the ocean floor may be reduced. Other species, such as crabs, shrimp and fish, leave the dead zone in order to survive but there is evidence that dead zones may harm growth rates. Ultimately, these shifts can ripple to the top of the food chain, with top predators needing to look elsewhere for their dinner.

What Causes The Dead Zone?

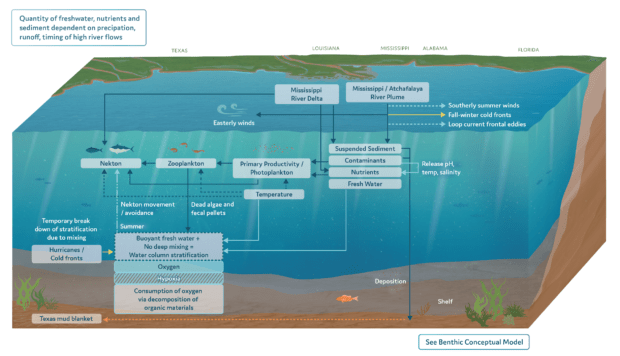

So far 2019 has been the wettest year ever measured in the Mississippi River’s drainage basin. Some areas experienced rain and snowfall that were two and a half times more than normal. Fields and forests were drenched while streams and rivers swelled out of their banks into communities and farms. Normally, the sediment, fresh water, and nutrients carried by the river are essential to build and sustain deltaic wetlands, fuel our estuaries and feed Gulf seafood and wildlife. These are unquestionably good things – but too much of any one thing can have unwanted consequences.

The same way that these fertilizers spur the growth of corn in a field, they spur the growth of microscopic algae in the Gulf’s surface waters. Algae is the base of a complex food web where it is consumed by small animals, that in turn are consumed by larger creatures such as shrimp and jellyfish, and so on right up the food chain to sea turtles, bluefin tuna, sperm whales and humans. So far, so good. But in the still, hot summer, the dense salty waters on Louisiana’s continental shelf become isolated from the fresh, oxygen-rich waters on the surface and trouble begins.

As the short-lived algae die, they sink to the bottom. There, another part of the food web kicks in, this one dominated by bacteria. In the process of consuming the dead algae raining down from above, the bacteria also consume all of the available oxygen in the deep water. In the absence of storms and intense waves to mix the oxygen-depleted deep waters and the oxygen-rich surface water, a low-oxygen “Dead Zone” develops along the bottom just off the coast of Louisiana and sometimes as far west as Texas.

This hypoxic zone may persist until fall’s weather fronts move through the area, mixing the water column, bringing oxygen to the seafloor.

Dead zones are expanding throughout the world. The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is the second largest in the world. This year, given the length of the flood on the Mississippi River and the volume of nutrient-laden water, the hypoxic area in the Gulf of Mexico covers an area of almost 7,000 square miles.

Reducing The Dead Zone:

The good news is that a mix of forest and riparian habitat restoration and agricultural practices can help prevent future dead zones by stopping fertilizer from reaching the Gulf. Here are five ways the National Wildlife Federation is working for wildlife:

1) DEFENDING THE CLEAN WATER ACT: The best way to improve water quality is to prevent pollution at its source. We work to protect and defend the Clean Water Act against a multitude of attacks from Congress and the Trump administration. Currently, the administration is attempting to remove important safeguards that have protected our nation’s wetlands and streams since the 1970s. The Clean Water Act serves as our first line of defense against water pollution, but it cannot do so if streams and wetlands aren’t legally covered under its protections.

2) WORKING WITH FARMERS: We work on-the-ground with farmers and landowners to promote responsible conservation practices, like planting cover crops and protecting prairie potholes and other marginal farmland important to wildlife. By conserving these soil and wildlife-friendly working lands, farmers can help ensure more excess fertilizer is absorbed and does not reach the Gulf.

We are also fighting unwise federal

policies, like the ethanol mandate. This EPA policy leads to the destruction of

vital wildlife habitat on working lands and a drop in soil health by creating

high demand for corn crops. This starts a vicious cycle: as soil health

plummets, more fertilizer is required. With the soil less able to absorb

fertilizer, more ends up in the Gulf, exacerbating the Dead Zone.

3) MAINTAINING CONNECTIONS BETWEEN RIVERS AND FLOOD PLAINS: We work to prevent the construction of water projects that would sever the connection between the river and its floodplain and destroy wetland habitat. In Missouri, we preserved the New Madrid Floodway a vital connection between the river and its floodplain that provide important fish and wildlife habitat and critical flood protection.

4) RESTORING THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER DELTA In Louisiana, we work to reconnect the Mississippi River with its delta by supporting the construction of sediment and freshwater diversions, designed to mimic the natural spring flood interrupted by levees. This restored coastal wetlands are vital fish and wildlife habitat and absorb nutrients before they are pushed out into the Gulf.

5) STOPPING CLIMATE CHANGE: Climate change shifts agricultural patterns and threatens the stability of aging flood control infrastructure like levees, dams, reservoirs, sewage treatment plants and more. The increasing frequency and intensity of weather events like hurricanes along the Gulf could make today’s several thousand square mile dead zone seem like a minor problem.