Managing weeds is one of the central responsibilities of growing crops, a task that asks for a considerable amount of labor, time, and tools. Since their development in the twentieth century, synthetic pesticides, including herbicides, have become a primary tool of weed management due to their cost-effectiveness, efficacy, and fewer labor demands.

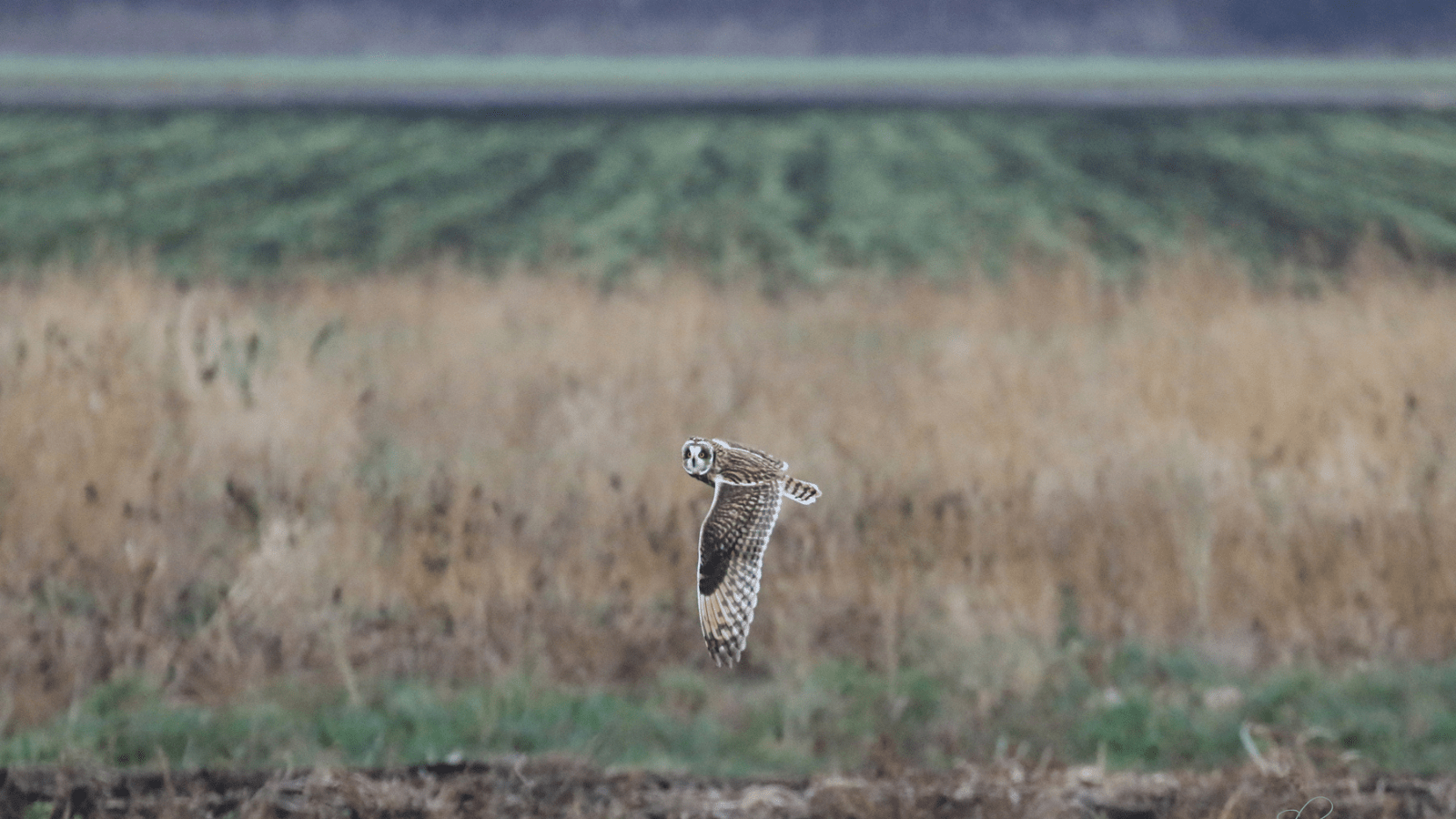

But, these herbicides often have dire ecological consequences that disrupt pollinator activities, soil health, waterways, and nearby wildlife. And, alongside these effects, weeds are becoming very adept at resisting herbicides within a few generations of their species’ lifespan, raising questions about the over reliance on herbicides for weed management particularly for farming. Implementing diverse tactics for weed control and deemphasizing herbicides would help farmers avoid the weed resistance cycle while promoting biodiversity.

Herbicide-Resistant Weeds

Regulated by the EPA, synthetic herbicides are chemical treatments designed to target plants that pose a problem for growers, often varying in application method and impact on weeds. For example, glyphosate, commonly known as RoundUp and one of the most popular herbicides used on American farms, is a broad spectrum herbicide, meaning it will target most plants. Dicamba, on the other hand, is an herbicide that is best effective on specific plants. However, growers across the U.S. are noticing that regardless of these differences, weeds are surviving herbicide treatments.

A recent article by Ohio’s Country Journal highlights the scale at which weeds continue to adapt to ensure their survival: “Herbicide resistance has steadily increased in the last 50 years since the time that herbicide application became a tool for farmers in the battle against weeds…In 2020 there were over 500 unique herbicide resistance cases globally.” The challenges of this resistance is competition for resources that hinder crop development and the introduction of plant diseases and pests, all of which can lead to insufficient crop yields.

To address the challenges presented by herbicide-resistant weeds, researchers, farmers, and extension agents suggest a variety of tactics, but the prevailing sentiment is to adopt a weed management strategy that integrates multiple methods of weed control to prevent over-reliance on one method. This approach is referred to as Integrated Weed Management (IWM) and has been adopted by some farmers in response to how problematic herbicide- resistant weeds have become.

Diversifying Weed Management

Integrated weed management (IWM) is a strategy that emphasizes a diversity of tools to control weeds beyond solely relying on synthetic chemical applications. To implement IWM, farmers must closely consider the local ecosystem, the particular traits of weed species, the level of weed presence, history of weed management strategies at the farm site, and other ecological and economic factors of weed control.

Because IWM does not prescribe specific methods of weed control, herbicides may very well be in a farmer’s toolbox, such as treating glyphosate-resistant weeds with another herbicide to which the weeds have not established resistance. Yet given the adverse ecological effects that herbicides can have on local biodiversity and wildlife, herbicide-resistant weeds offer an opportunity to incorporate non-herbicide driven weed management to meet both agricultural and ecological needs.

Reduced application of herbicides coupled with other management practices such as crop rotation, cover crops, staggered planting times, and mulching can limit the proliferation of synthetic chemicals that build weed resistance, and could harm local ecosystems.

Committed to promoting sustainable weed management practices, The National Wildlife Federation continues to advocate for more effective ecological risk evaluations that ensure that wildlife is protected against harmful chemicals like pesticides.